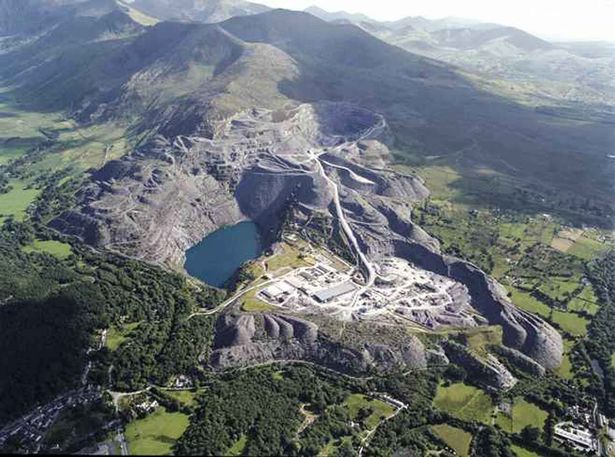

The Penrhyn Quarry at Bethesda

Penrhyn Quarry pictured in 1900

The Quarry since its beginning down the centuries, has developed to such an extent that dozens of farm-houses, homes and bridges have been buried from time to time under its rubble. I am sure that at the beginning no one thought that this kind of development would take place. On the other hand, whole villages have grown in the area by the influx of people from surrounding counties. Not only Bethesda, but the other villages like Tregarth, Rhiwlas, Carneddi, Gerlan, Llanllechid and Llandegai. By today they are established communities. The Quarry itself occupies acres of land, and half a mountain has been blown away to produce slates. The Fronllwyd mountain is now half its original size. The land where sheep used to graze, and where the men cut peat, and the women gathered bilberries is no longer there. Instead, heaps of rubble cover the land and beauty has given way to ugliness. Even the original church of St. Anne’s suffered a similar fate. This was a little church, where in all probability, my grandparents on my father’s side were married and worshipped. It is difficult to imagine a live church buried under a rubble of slates.

The old church was closed with the last service on May 3rd 1865. But through the generosity of Lord Penrhyn a new church was built at a place called today Bryn Eglwys. The first Vicar was Canon Walter Jones, whose daughter Gwendoline married The Reverend Basil Jones, the Vicar of Llandegai when I was a small boy. After Basil died, she very kindly presented me with his private Communion set which I have used almost daily for the past sixty years, and still in my possession today.

The new Churchyard at Bryn Eglwys contains the remains of many of my relatives. My brother Reynold and his wife Annie are buried there and his daughter Heulwen. My grandparents are probably there as well as are my Uncle William and his wife, his daughter, Edith and her husband Wil.

The Penrhyn Quarry employed some 2,800 men who, with gunpowder and crowbar, hammer and chisel, blasted and coaxed the slate from the mountain. Its galleries varied in height from 36 to 66 feet (with an average of 54 feet), in breadth from the wide platforms of 45 feet to narrow ledges no wider than 6 feet. When levering blocks of slate from the rock face, men would hang over the precipitous and shattering side, with a rope of hemp looped round their bodies. Every hour a bell rang out to signal them to shelter, one minute later on the signal of a second bell, fuses would be lit all over the Quarry, followed by a fall of rock, shattering in the explosions. Four minutes later another bell would sound summoning them back to work. The slabs were prised away from the rock and sent to the sheds to be dressed and split into slates. Wheldon and other members of the family worked on the rockface, while Cyril, BRW, and Wil worked in the sheds. The men worked in crews of three or four, half the crew on the rockface, the other half in the sheds, but each crew entered into a separate working arrangement with the Management. There were, also other type of workmen with no special skill, rubbishmen and apprentices etc. My father did a special kind of work, as did a number of other men, being responsible for transporting the slabs of rock on wire ropes from the pits to the sheds. Whatever the nature of the work, it was hard and heavy. There was no comfort whatsoever from the heat of the summer or from the bitter cold of winter. Even the sheds, although under cover were cold and draughty. In addition, the work was highly dangerous. My Uncle William, my father's brother was killed by a fall of rock in the late twenties. So dangerous was the work that a special hospital was built to cope with the sick and wounded, and with its own resident doctor. By today the hospital is not longer in use, and the number of workmen in the Quarry nowadays is no more than two or three hundred. With the advent of roof tiles, sadly the days of slate quarrying are slowly coming to an end.

HLW

The History Of Penrhyn Quarry

One of the highlights of preparing this website is learning a great deal about my family and the context in which they led their lives. The notes below tell the story of the Quarry, in particular the very sad division in the community caused by different allegiances in the strike of 1900. My father told me that our family were on the side of those who did not strike. He also told me that it was a commonly held belief in Tregarth that the cottages in Ffrwd Galed where allocated to those who had remained loyal to Lord Penhryn. Dad was always anti the abuse of union power in outlook, an attitude no doubt learned from his father.

The first reference to slate extraction at Penrhyn is from 1570, when the quarry is mentioned in a Welsh poem. The quarry was developed in the 1770s by Richard Pennant, later Baron Penrhyn. Much of his early working was for local use only as no large scale transport infrastructure was developed until Pennant's involvement. From then on, slates from the quarry were transported to the sea at Port Penrhyn on the narrow gauge Penrhyn Quarry Railway built in 1798, one of the earliest railway lines. In the 19th century the Penrhyn Quarry, along with the Dinorwic Quarry, dominated the Welsh slate industry.

The quarry holds a significant place in the history of the British Labour Movement as the site of two prolonged strikes by workers demanding better pay and safer conditions. The first strike lasted eleven months in 1896. The second began on 22 November 1900 and lasted for three years. Known as "The Great Strike of Penrhyn", this was the longest dispute in British industrial history. During the strike, the community was divided between those who laid down their tools and those broke the picket line, with many locals writing "Nid oes bradwr yn y Ty hwn" or "There are no traitors in this house" in their front windows.

The 1900-03 strike, or lock out, was a culmination of several years of dissatisfaction and unrest in the quarrying industry in the Ogwen Valley. Centered on Union rights, pay and working conditions the Great Strike was a bitter battle between Lord Penrhyn and the quarry workers which ripped apart a community and changed this part of North Wales forever.

It was the after effects of shorter disputes in 1874 and 1896 that led to the formation of the North Wales Quarrymen’s Union. These disputes came about following discussions with regards to the rights of workers to attend a Labour Day festival and the issue of the ‘bargain’. The 'bargain' was a system that protected the quarrymen’s earnings against the difficulties of working with rock of variable quality and allowed them to regard themselves as contractors rather than employees.

Lord Penrhyn and his agent E. A. Young had been fighting against the unionisation of their workforce and the tradition of the ‘bargain’ for several years. They had been trying everything they could to eliminate the North Wales Quarrymen's Union's influence within the quarry.

In April 1900 quarry manager Mr Emilieus Young announced trade union contributions would not be collected at the quarry.Tensions turn to violence.Tensions between owner and workers finally boiled over on 26 October 1900, in violence against a number of contractors who had struck a bargain.

Lord Penrhyn pressed assault charges against 26 quarrymen and they were dismissed from the quarry, even before their case was heard before the Magistrates Court.When the matter came to court, the Penrhyn quarrymen, in what became an iconic show of solidarity, marched to Bangor to show their support to the accused men and were all suspended from their work for two weeks. It was reported that as they marched past the gates of the castle, they turned their heads to face the other way.At the hearing only 6 of the 26 of the accused men were found guilty of the charges and fined. In response to the growing tension the Chief Constable of the County called in military forces and was condemned by various public bodies as well as his own County Council.The suspended quarrymen returned to work on November 19, 1900 but eight banks (or ponciau as they were known locally) were not let out to be worked, leaving 800 men without a bargain.Three days later, on 22 November, 2,000 quarrymen arrived as usual at the quarry but refused to work until the other 800 had struck a bargain. That morning Young gave them an ultimatum - “Go on working or leave the quarry quietly”. They walked out and the Great Strike of 1900-03 had started. Things would never be the same again.

A month later Young offered new terms to the quarrymen, but they were accepted by just 77 workers and refused by 1,707. By mid-January, the closure was complete with workers from Porth Penrhyn being dismissed.

Re-opening the quarry and rifts in the community

On 20 May, Young release a poster stating that the quarry would re-open on 11 June to all employees who had applied to the office and been accepted. On 11 June 1901 as stated on the poster, the Penrhyn Quarry was re-opened and an invitation was extended to quarrymen approved by the quarry office to return to work.

Four hundred men returned, receiving a sovereign each from Lord Penrhyn and the promise of a 5% pay increase. This would be known as the infamous ‘Punt y gynffon’ (The tail pound).

The local community was divided in two: strikers and ‘cynffonwyr’ (the ones who had accepted the ‘Tail pound’). In a turbulent meeting of the strikers that same evening, it was decided that posters bearing the words: Nid Oes Bradwr yn y Ty Hwn (There is no traitor in this house) be printed and shown in a window of every striker's home.These cards were displayed for two years, until the end of the strike. Taking a card from the window was a sign that a worker had broken the strike.This caused heightened tensions in the area that turned to violence. Local pubs and the houses of the men that had returned to work were smashed. The names of those who had broken the strike were published in the Y Werin and Eco newspapers.

In response to the violence and tension, soon afterwards the Chief Constable of Caernarfonshire sent troops into the village and a Justice of the Peace arrived to read the Riot Act to the striking men formally warning the protesters to disperse and authorising the use of force if necessary.

Desolate Bethesda

By the end of 1901, Bethesda was desolate. Devoid of work, money and food; poverty grew and fever struck the schools.

By 1902, 700 men had begrudgingly returned to the quarry and another 2,000 had moved from the area. Most went to work in the coalfields of South Wales – and the community of Bethesda had changed forever.

In the longer term the dispute cast the shadow of unreliability on the North Welsh slate industry, causing orders to drop sharply and thousands of workers to be laid off.

In 2003, on the centenary of the strike, the T&G unveiled a plaque in memory of those who participated.

From 1963 until 2007 it was owned and operated by Alfred McAlpine PLC.

In 2007 it was purchased by Kevin Lagan and renamed Welsh Slate Ltd. Kevin Lagan and his son Peter are now directors of Welsh Slate Ltd which also includes the Oakeley quarry in Blaenau Ffestiniog, the Cwt Y Bugail quarry and the Pen Yr Orsedd quarry. The Lagan Group was itself acquired by the Leicestershire-based Breedon Group in 2018.

A part of the site no longer in use for slate extraction is the site of a new adventure tourism facility operated by Zipworld. The zip line Velocity 2 flies above an abandoned flooded quarry.

Welsh slate such as that quarried at Penrhyn was designated by the International Union of Geological Sciences as a 'Global Heritage Stone Resource' early in 2019 in recognition of its significant contribution to world architectural heritage.

Quarrying Slate, unchanged for 100 years

Zip World seems a world away from those days..